(This post was originally published in Generalized Method of Moments (GMM) in R (Part 1 of 3). I rewrite it here to utilize markdown and latex for scientific post.)

In this post basic concepts of Generalized Method of Moments (GMM) are introduced and the applications in R are also discussed. Interested audience can also refer to the video uploaded by Morten Nyboe Tabor (The source of the cover letter is also from his video). Well, the first stuff to be clarified is that GMM here is the abbreviation for Generalized Method of Moments in Econometrics but NOT Gaussian Mixture Modeling in machine learning. Even though machine learning and furthermore deep learning are also the hot and popular topics in Economics and business schools, traditional theory-driven empirical thoughts are still the central parts of courses. During my teaching tour in the university, clarification of the difference between causal inference and prediction is always the first topic. In general, even the well trained machine learning model cannot directly tell the causal inferences. Nowadays, extraordinary tool of SHAP can try decomposing the predicted value of individual observation into the contributions of every feature value. However, in most of the time only correlation or association can be interpreted. The detailed discussion about such issue can be found in Be Careful When Interpreting Predictive Models in Search of Causal Insights authored by Scott Lundberg (2021), also the key author of the literatures about SHAP (Scott Lundberg, 2017). However, in practice Economic policy makers in the governments or the managers in the corporations always consider policy interventions. Therefore, the evaluation of the effects on specific targets from the change of some policy in the counterfactual analysis is usually preferred in articles, reports, and academic papers. However, without the examination of the backgrounds and theories, results about SHAP values for the trained machine learning model can be misinterpreted as causal inference and misleading policy suggestions are generated. Just take the case shown in that post by Scott Lundberg for example, the trained model just indicates the positive correlation between the number of bugs reported and the individual’s intention to renew the product. Do you think the instant suggestion is to ask the technical staffs to bring in more bugs in the future to boost the sales? Therefore, a series concepts about causal inferences, Economics or business theories, and the empirical strategies are always discussed in Econometrics classes. In order to facilitate the evaluation of the policy within counterfactual analysis, theories are seriously discussed to generate the parametric equations. From the data samples, appropriate estimation approaches are implemented to estimate the fixed but unknown parameters of meanings. Statistical inferences are thus discussed about causal inferences. This is the usual path about empirical studies in Economics and business studies.

Generalized Method of Moments (GMM) is an estimation approach for the unknown parameters within the specified model. Interestingly, GMM is usually not discussed especially in the first course of Econometrics probably because of the time limitation, and most of the students not pursuing an academic career or PhD usually would like to take ONLY ONE (or better zero) Econometrics course. That is the basic reason for most of the students in business school to feel unfamiliar with GMM. However, all of them just apply GMM in their projects or reports, since Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) and Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) can be just viewed as GMM. GMM is actually appealing not only because of its conceptual ideas to include other extremum estimators (e.g. OLS and MLE) into the omnibus system but also because of its flexibility about model constructions. In this part 1 of 3, I mainly focus on the basic ideas of GMM and how GMM is usually more robust for statistical inferences using simple linear regression (OLS) as the example. In part 2 of 3, Quasi-Maximum Likelihood Estimate (QMLE) is discussed for the relation between MLE and GMM. In part 3 of 3, GMM is introduced for the structural models, so the comparison between Two-Stage Least Squares (2SLS) Regression and GMM is discussed. Please check my Github for the codes and examples used in these posts.

What are the moments?

Just take the simple example as the beginning to illustrates what the (population) moments are. Actually, in probability theory and statistics, (population) moments are referring to population mean or expectation, which is usually the key population parameter of interest. For example, suppose \(x\) is random variable with normal distribution, then its mean is \(\mathbb{E}[x]=\mu\). On the other hand, theoretically the population mean or expectation can be implemented on arbitrary function of random variables. For example, with simple conversion we can also have \(\sigma^2=\mathbb{E}[(x-\mu)^2]\). Up until now we have got two equations, or say, moment conditions, for two parameters σ and μ. With simple computation we can have the solutions for them: \(\mu=\mathbb{E}[x]\) and \(\sigma^2=\mathbb{E}[(x-\mathbb{E}[x])^2]\). Such simple computation seems not to be helpful to get the values for \(\mu\) and \(\sigma^2\), since we have no idea about the distribution about \(x\) and then cannot compute the corresponding population mean or expectation.

However, probability theory and statistics provide the ideas or thoughts to infer the population from the random samples. For simplicity, \(T\) (independent and identically distributed) iid random samples are collected for such \(x\) with normal distribution. The question is how can we utilize such samples to get the sensible estimates of \(\mu\) and \(\sigma^2\)? Here we have the powerful fundamental principle: Law of Large Number (LLN): sample mean converges to population mean. Admittedly, several technical issues are fully discussed in textbooks such that we at least have several versions of LLN. Here we just try making our lives easier to get the essential sense of LLN. Therefore, we can just just substitute the sample mean (moment) for population mean (moment) in the above simple solutions:

\[\hat{\mu}=\frac{1}{T}\Sigma x_i\] \[\hat{\sigma^2}=\frac{1}{T}\Sigma[x_i-\hat{\mu}]^2\]Now, we just obtain the estimators for \(\mu\) and \(\sigma^2\) based on two moment conditions and the random samples. Usually we call such estimator as Method of Moments (MM) Estimator. I just remember in my first course of statistics in the university the instructor just said MM is much simpler than MLE since bundles of probability density functions are ignored to obtain the estimator. The direct inference about MM (and also GMM) is that ONLY moment conditions are assumed but no distributional presumptions are required. Such property determines that MM (and also GMM) is relatively robust to incorrect assumptions about distributions on the data generation process. In most of the empirical studies with causal inferences as the central targets, robustness checks are always required to exhibit.

What is the Idea behind the GMM Objective Function

In this section, GMM is introduced to indicate it is more generalized than MM. Just briefly review the above example for MM estimator. At the very beginning we just have two unknown parameters to estimate, and then try seeking for two moment conditions. In literature, this case is called just-identified, meaning that we have just enough information (two moment conditions) to solve for the two estimators. On the other hand, what if only one moment condition is given? This case is called not-identified, indicating that the estimators cannot be obtained for unique solution. The most interesting case is over-identified, in which the number of moment conditions is larger than the number of unknown parameters to be estimated. Just follow the above example, actually one more moment condition can be given

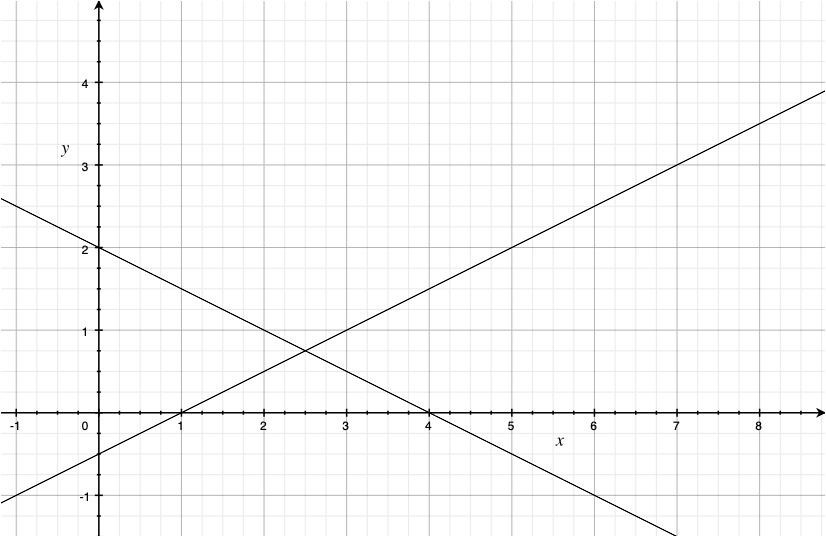

\[\mathbb{E}\left[g\left(\theta, x_{i}\right)\right] \equiv \mathbb{E}\left[\begin{array}{c} \mu-x_{i} \\ \sigma^{2}-\left(x_{i}-\mu\right)^{2} \\ x_{i}^{3}-\mu\left(\mu^{2}+3 \sigma^{2}\right) \end{array}\right]=0\]The third line is about the third moment of normal random variable. In general, it should be advantageous to have more information to obtain the estimators for the unknown parameters. However, in practice substituting the sample moment conditions for the population moment conditions yields to the system of equations which may not have the solutions, just because three equations are given for only two unknowns. The following picture is the straightforward illustration about the difficulty: in general we cannot find exactly the same ONE point on the x-axis to make two lines equal to zero simultaneously. So, what should we do?

If the population moment conditions are valid, then the sensible estimators based on them should make all corresponding sample moment conditions as close to zeros as possible. Therefore, we can just reformulate the problem about solving for the system of equations to the optimization problem, and the objective function is

\[\min _{\theta} Q_{T}(\theta)=\min _{\theta} g_{T}(\theta)^{\prime} W_{T} g_{T}(\theta)\]where

\[g_{T}(\theta) \equiv \frac{1}{T} \sum_{t=1}^{T} f\left(w_{t}, z_{t}, \theta\right)\]is the vector function for such three sample moments. That is, the estimators for the unknowns should be the minimum of such weighted average of all sample moment conditions, and the estimators are called Generalized Method of Moments (GMM) estimators. One point should be noted that MM estimators are just he special cases of GMM estimators. In the just-identified case the above objective function should have the minimum value of zero such that the optima are the MM estimators to make the system of equations on the sample moment conditions to equal to zeros. This is also the characteristic to help check whether the minimization process generates errors for just-identified case.

Efficient GMM

In this section, the choice of the best weights is discussed. From the objective function, one can easily find that the optimum actually depends on both the sample moment conditions and the choice of weights on every moment. The question is, what weights should be chosen? In order to answer this question, we need to have the target or criterion to evaluate the choice, and efficiency is the general point under consideration. Generally speaking, point estimates are not enough and follow-up statistical inferences (e.g. hypothesis testing and confidence interval) are usually required in terms of confirmatory analysis. It follows that the sampling distribution of the estimator is usually taken into account. Roughly speaking, the smaller the variance of the estimator the more precise. Just skipping the tedious matrix calculus derivation, the efficient GMM estimator can be obtained when the inverse of the covariance matrix of moment conditions is used as the weights. (Verbeek, M., 2004) That is,

\[W^{o p t}=\left(E\left\{f\left(w_{t}, z_{t}, \theta\right) f\left(w_{t}, z_{t}, \theta\right)^{\prime}\right\}\right)^{-1}\]The rationale is also straightforward. Just take the above example, one can imagine that adding more and more moment conditions is possible, e.g. the forth moment, the fifth moment, etc. of xᵢ. However, do you think they are equally important? Theoretically, if some moment condition has large variance, it is sensible to view it not stable or reliable. That is, one should put smaller weight on such moment condition. Actually, higher order moments are more unstable in the sense of larger variances, so smaller weights should be put on them to hold the stability of the estimators (as small variance as possible).

In terms of operationalization, we need to have the feasible estimate of such weight matrix, since it depends on the unknowns. Therefore, the estimation strategy is two-step. In the first step, we just use the equal weights (identity matrix) to get the estimates of all unknowns. With such estimates, which are still the consistent estimates of unknowns, we can get the following consistent estimates for the weights matrix:

\[W_{T}^{o p t}=\left(\frac{1}{T} \sum_{t=1}^{T} f\left(w_{t}, z_{t}, \hat{\theta}_{[1]}\right) f\left(w_{t}, z_{t}, \hat{\theta}_{[1]}\right)^{\prime}\right)^{-1}\]Of course, this result also depends on the assumption that no autocorrelation among the samples, but allows for different variances across samples. Therefore, we have the complete expression about the sampling distribution for the efficient GMM:

\[\begin{gathered} \sqrt{T}\left(\hat{\theta}_{G M M}-\theta\right) \rightarrow \mathcal{N}(0, V) \\ V=\left(D W^{o p t} D^{\prime}\right)^{-1} \\ D=E\left\{\frac{\partial f\left(w_{t}, z_{t}, \theta\right)}{\partial \theta^{\prime}}\right\} \end{gathered}\]where \(D\) is the derivative matrix to measure the sensitivity of the moment condition on the change of unknowns and in practice sample moments are used instead of the population moments for the consistent estimates. Luckily, in R we have the package gmm to handle the above optimization process and the computation of the standard errors for statistical inference (Chaussé, P., 2021).

# Simulate One column data

# Reproducible

set.seed(123)

# Generate the data from normal distribution

n <- 200

x <- rnorm(n, mean = 4, sd = 2)

# set up the moment conditions for comparison

# MM (just identified)

g0 <- function(tet, x) {

m1 <- (tet[1] - x)

m2 <- (tet[2]^2 - (x - tet[1])^2)

f <- cbind(m1, m2)

return(f)

}

# GMM (over identified)

g1 <- function(tet, x) {

m1 <- (tet[1] - x)

m2 <- (tet[2]^2 - (x - tet[1])^2)

m3 <- x^3 - tet[1] * (tet[1]^2 + 3 * tet[2]^2)

f <- cbind(m1, m2, m3)

return(f)

}

print(res0 <- gmm(g0, x, c(mu = 0, sig = 0)))

print(res1 <- gmm(g1, x, c(mu = 0, sig = 0)))

One can check the detailed results

summary(res0)

The results are

Call:

gmm(g = g0, x = x, t0 = c(mu = 0, sig = 0))

Method: twoStep

Kernel: Quadratic Spectral

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

mu 3.9812e+00 1.2373e-01 3.2177e+01 3.7093e-227

sig 1.8814e+00 9.9904e-02 1.8832e+01 4.1605e-79

J-Test: degrees of freedom is 0

J-test P-value

Test E(g)=0: 0.000702626643691055 *******

#############

Information related to the numerical optimization

Convergence code = 0

Function eval. = 67

Gradian eval. = NA

and

summary(res1)

The results are

Call:

gmm(g = g1, x = x, t0 = c(mu = 0, sig = 0))

Method: twoStep

Kernel: Quadratic Spectral(with bw = 0.71322 )

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

mu 3.8939e+00 1.2032e-01 3.2364e+01 8.9213e-230

sig 1.7867e+00 8.3472e-02 2.1405e+01 1.1937e-101

J-Test: degrees of freedom is 1

J-test P-value

Test E(g)=0: 2.61527 0.10584

Initial values of the coefficients

mu sig

4.022499 1.881766

#############

Information related to the numerical optimization

Convergence code = 0

Function eval. = 63

Gradian eval. = NA

Such simple example just indicates how to use the gmm package to conduct GMM. The key point is to setup the function about moment conditions, like g0 and g1 . The arguments are the parameters tet and data x , and the output is that \(T × q\) matrix, where \(q\) is the number of the moment conditions. Actually, this function need to export the results of q moment conditions for each sample (row). With this function into gmm , the package will do the rest to get the estimates and the standard errors. The following example about regression can indicate more details.

OLS as GMM

In this part, a more realistic example is discussed to illustrate the relation between OLS and GMM. The short answer is, OLS estimator is actually the GMM estimator. In order to explain this issue, it is beneficial to illustrate the population moment conditions embed in the linear projection model which inspires OLS.

Suppose a linear predictor for \(y\) is a function of the form \(\boldsymbol{x}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{\beta}\) for some \(\boldsymbol{x}\). How can we make such linear predictor sensible to be the best? Actually We can have the sensible objective function, called mean squared prediction error (MSE): \(S(\boldsymbol{\beta})=\mathbb{E}\left[\left(y-\boldsymbol{x}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{\beta}\right)^{2}\right]\).The Best Linear Predictor of \(y\) given \(\boldsymbol{x}\) is \(\mathscr{P}[y \mid \boldsymbol{x}]=\boldsymbol{x}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{\beta}\) where \(\boldsymbol{\beta}\) minimizes the mean squared prediction error \(S(\boldsymbol{\beta})=\mathbb{E}\left[\left(y-\boldsymbol{x}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{\beta}\right)^{2}\right]\). Please note that the minimizer

\[\boldsymbol{\beta}=\underset{\boldsymbol{b} \in \mathbb{R}^{k}}{\operatorname{argmin}} S(\boldsymbol{b})\]is called the Linear Projection Coefficient. One can easily verify that the minimizer \(\boldsymbol{\beta}\) is just to make

\[\begin{aligned} \mathbb{E}[\boldsymbol{x} e] &=\mathbb{E}\left[\boldsymbol{x}\left(y-\boldsymbol{x}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{\beta}\right)\right] \\ &=\mathbb{E}[\boldsymbol{x} y]-\mathbb{E}\left[\boldsymbol{x} \boldsymbol{x}^{\prime}\right]\left(\mathbb{E}\left[\boldsymbol{x} \boldsymbol{x}^{\prime}\right]\right)^{-1} \mathbb{E}[\boldsymbol{x} y] \\ &=\mathbf{0} \end{aligned}\]from the first order condition of such optimization problem. Look, we have just derived the vector function about the population moment conditions:

\[\mathbb{E}\left[x_{j} e\right]=0, k = 1, ..., k\]where the projection error is defined by construction as the difference between \(y\) and \(\mathscr{P}[y \mid \boldsymbol{x}]\): \(e=y-{\boldsymbol{x}}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{\beta}\). Just follow the logic of GMM, the corresponding sample moment conditions can be obtained. One more stuff should be noted that this is the case of MM since the number of moment conditions are the same as the number of unknowns:

\[\frac{1}{T} \Sigma\left(\left[\boldsymbol{x}_{\boldsymbol{i}}\left(y_{i}-\boldsymbol{x}_{i}^{\prime} \hat{\boldsymbol{\beta}}\right)\right]\right)=\mathbf{0}\]On the other hand, the above linear projection model just authorize OLS given the samples. On the other hand, the implication of OLS estimators also point to exactly the same system of equations of as the above:

\[\frac{1}{T} \Sigma\left(\left[\boldsymbol{x}_{\boldsymbol{i}}\left(y_{i}-\boldsymbol{x}_{i}^{\prime} \hat{\boldsymbol{\beta}}\right)\right]\right)=\mathbf{0}\]Therefore, OLS estimators are just the GMM estimators, and they should give exactly the same estimates given the same set of samples. However, one tricky point is that they have distinct covariances without special settings. The basic reason is from the sampling distribution of efficient GMM in the case of linear regression:

\[V\{b \mid X\}=\left(X^{\prime} X\right)^{-1} X^{\prime} \operatorname{Diag}\left\{\sigma_{i}^{2}\right\} X\left(X^{\prime} X\right)^{-1}\]This is the result of the covariance matrix for efficient GMM estimator under the case of linear regression. By default, efficient GMM estimator just allows for the heteroskedasticity across samples. That is, the middle part is

\[\Sigma \equiv \frac{1}{N} X^{\prime} \operatorname{Diag}\left\{\sigma_{i}^{2}\right\} X=\frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^{N} \sigma_{i}^{2} x_{i} x_{i}^{\prime}\]and in practice we also have

\[S \equiv \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^{N} e_{i}^{2} x_{i} x_{i}^{\prime}\]and

\[\begin{aligned} \hat{V}\{b\} &=\left(X^{\prime} X\right)^{-1} \sum_{i=1}^{N} e_{i}^{2} x_{i} x_{i}^{\prime}\left(X^{\prime} X\right)^{-1} \\ &=\left(\sum_{i=1}^{N} x_{i} x_{i}^{\prime}\right)^{-1} \sum_{i=1}^{N} e_{i}^{2} x_{i} x_{i}^{\prime}\left(\sum_{i=1}^{N} x_{i} x_{i}^{\prime}\right)^{-1} \end{aligned}\]Actually this covariance matrix is just the White (1980) heteroskedasticity robust covariance for OLS estimator. However, the default OLS covariance in packages usually assume homoskedasticity with the form

\[\hat{\sigma^2}X^{\prime}X\]Therefore, even OLS estimators are just he GMM estimators in linear regression, but the package for GMM usually generates the more robust covariance matrix than those for OLS. In the jupyter notebook, the data about R&D expenditures and patents are used to illustrate this point. Please also check Section 7.3.2 of A Guide to Modern Econometrics (2nd edition) about the details of the data.

# Simple regression can be implemented

lm_res <- patents_df %>%

lm(p91 ~ lr91 + aerosp + chemist + computer + machines +

vehicles + japan + us, data = .)

summary(lm_res)

and the results are

Call:

lm(formula = p91 ~ lr91 + aerosp + chemist + computer + machines +

vehicles + japan + us, data = .)

Residuals:

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-355.26 -54.78 -1.84 34.98 624.22

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) -234.631 55.543 -4.224 3.88e-05 ***

lr91 65.639 7.907 8.302 2.91e-14 ***

aerosp -40.771 35.700 -1.142 0.2550

chemist 22.915 26.640 0.860 0.3909

computer 47.370 27.834 1.702 0.0906 .

machines 32.089 27.941 1.148 0.2524

vehicles -179.949 36.731 -4.899 2.21e-06 ***

japan 80.883 41.060 1.970 0.0505 .

us -56.964 28.794 -1.978 0.0495 *

---

Signif. codes: 0 ‘***’ 0.001 ‘**’ 0.01 ‘*’ 0.05 ‘.’ 0.1 ‘ ’ 1

Residual standard error: 114.8 on 172 degrees of freedom

Multiple R-squared: 0.4471, Adjusted R-squared: 0.4213

F-statistic: 17.38 on 8 and 172 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16

On the other hand, GMM estimation is similar to the example in the last part:

# Generate the data with all needed variables only

df_n <- patents_df %>%

select(

p91, lr91, aerosp, chemist, computer, machines,

vehicles, japan, us

) %>%

mutate(const = 1) %>%

# Please hold the order as previous glm() to facilitate comparison

select(

p91, const, lr91, aerosp, chemist, computer, machines,

vehicles, japan, us

)

## Need to converse the tibble class to dataframe

df_n <- as.data.frame(df_n)

mom_lm <- function(beta, df) {

# df is the data frame with first column as dv

# This function returns n * q matrix

# Each column is one moment condition before taking sample average

# There are totally q moment conditions

y <- as.numeric(df[, 1])

x <- data.matrix(df[, 2:ncol(df)])

# Refer to moment conditions of QMLE

m <- x * as.vector(y - x %*% beta)

return(cbind(m))

}

set.seed(1024)

gmm_lm_mds <- gmm(mom_lm, df_n, rnorm(length(coef(lm_res))),

wmatrix = "optimal",

vcov = "MDS",

optfct = "nlminb",

control = list(eval.max = 10000)

)

summary(gmm_lm_mds)

The results are

Call:

gmm(g = mom_lm, x = df_n, t0 = rnorm(length(coef(lm_res))), wmatrix = "optimal",

vcov = "MDS", optfct = "nlminb", control = list(eval.max = 10000))

Method: twoStep

Kernel: Quadratic Spectral

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

Theta[1] -2.3463e+02 7.3190e+01 -3.2058e+00 1.3468e-03

Theta[2] 6.5639e+01 1.2913e+01 5.0833e+00 3.7097e-07

Theta[3] -4.0771e+01 1.9869e+01 -2.0521e+00 4.0164e-02

Theta[4] 2.2915e+01 2.4433e+01 9.3787e-01 3.4831e-01

Theta[5] 4.7370e+01 4.0565e+01 1.1678e+00 2.4291e-01

Theta[6] 3.2089e+01 2.4385e+01 1.3159e+00 1.8820e-01

Theta[7] -1.7995e+02 4.3154e+01 -4.1699e+00 3.0474e-05

Theta[8] 8.0883e+01 7.5709e+01 1.0683e+00 2.8537e-01

Theta[9] -5.6964e+01 3.6552e+01 -1.5585e+00 1.1913e-01

J-Test: degrees of freedom is 0

J-test P-value

Test E(g)=0: 4.08752755490864e-14 *******

#############

Information related to the numerical optimization

Convergence code = 0

Function eval. = 66

Gradian eval. = 590

Message: X-convergence (3)

One can find that both OLS and GMM can show the same point estimates consistent with our discussion. On the other hand, their standard errors differ. Actually, we can get the White robust standard errors using

# The estimates of the above GMM are the same as those in lm

# The sd of the above GMM are the white heterosketicity robust cov for linear regression

diag(vcovHC(lm_res, type = "HC0"))^0.5

and the results are

(Intercept)73.1895474823068

lr91 12.9127608451989

aerosp 19.8685659210385

chemist 24.4331404653491

computer 40.5652626257489

machines 24.3850596348934

vehicles 43.1544093699569

japan 75.7092057725459

us 36.5516092451842

That is, the White covariance is the same as that of GMM, consistent with out discussion again.

Summary

The key purpose of this post, or a series of these posts, are to give the introduction of GMM with minimum mathematics and maximum conceptual ideas. In general, reviews of such series of posts about GMM can probably help build the uniform system about extremum estimators for the unknown parameters in Econometrics. Especially from the discussion, it is expected that one can get the hints to comprehend the problems in different ways. For example, audience may remember OLS estimator is still asymptotically normal without the normal assumption on projection error and one explanation is GMM estimator is asymptotically normal only with the moment conditions valid. On the other hand, one can also conceive that gmm package in R is powerful to conduct GMM procedure with minimum coding efforts. Several points about the application of gmm can be also raised here:

-

wmatrixshould be set"optimal"(by default) whenever possible such that the optimal weights are used for efficiency. At the same time, two-step estimation will be applied accordingly to employ the consistent estimate of the weights. -

The setup of

vcovis tricky. One can easily check the expression of covariance of EfficientGMM estimator in Page 151 of A Guide to Modern Econometrics. The tricky point is about the assumption of \(W^{o p t}\). Please check section 1.1 of Generalized Method of Moments with R, and one can find the possible options. Gernally,"MDS"for martingale difference sequence which allows for heteroskedaticity should be used at least. In terms of the case of linear regression, such covariance matrix from GMM should be the same as the WhiteHC0version of the heteroscedasticity consistent covariance matrix (HCCM) estimator. Also, in Marno Verbeek’ book A Guide to Modern Econometrics, he also suggests the application of at least such assumption for robust standard error. In order to replicate the results in Marno Verbeek’ book A Guide to Modern Econometrics, this option will be used. However, thegmm()function by default employs"HAC", which assumes weakly dependent process. Actually this should be more stable than"MDS"in the sense that"HAC"can be robust to both heteroskedasticity and autocorrelation. -

In https://github.com/AlfredSAM/medium_blogs/blob/main/GMM_in_R/GMM_in_R.ipynb detailed discussion to replicate covariance of OLS estimator under GMM settings is illustrated but of little use in practice.

-

Please make sure that

optfctshould be set as"nlminb"instead of the default"optim", which will generate the incorrect results. In later posts, this point will be highly discussed.

References

-

Chaussé, P. (2021). Computing generalized method of moments and generalized empirical likelihood with R. Journal of Statistical Software, 34(11), 1–35.

-

Chausse, P., & Chausse, M. P. (2021). Package ‘gmm’.

-

Verbeek, M. (2004). A Guide to Modern Econometrics (2nd edition). ERIM (Electronic) Books and Chapters. John Wiley&Sons, Chichester.

-

Hansen, Bruce E. (2021). Econometrics. Typescript, University of Wisconsin. Princeton University Press, forthcoming.

-

Hansen, Bruce E. (2021). Probability and Statistics for Economists. Typescript, University of Wisconsin. Princeton University Press, forthcoming.

-

Lundberg, S., & Lee, S. I. (2017). A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. arXiv preprint arXiv:1705.07874.

-

Lundberg, S., & Lee, S. I. (2021). Be Careful When Interpreting Predictive Models in Search of Causal Insights. Towards Data Science.

-

White, H. (1980). A heteroskedasticity-consistent covariance matrix estimator and a direct test for heteroskedasticity. Econometrica: journal of the Econometric Society, 817-838.